At around 10 AM on Wednesday, February 5, 2026, a dynamite explosion ripped through an illegal coal mine in the Thangsku area of Meghalaya's East Jaintia Hills district. Eighteen workers — most of them migrant laborers from neighboring Assam — were killed. Eight more remain missing. Rescue operations by NDRF and SDRF teams were hampered by the mine's remote location, accessible only by four-wheel-drive vehicles over 25 kilometers of unpaved roads from the district headquarters.

District police chief Vikash Kumar told AFP that the explosion was likely caused by dynamite, with forensic investigation underway. The Washington Post described the mine as an illegal "rat-hole" operation — narrow tunnels barely 3-4 feet wide, dug into hillsides without ventilation, structural support, or safety equipment of any kind.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced an ex-gratia of Rs 2 lakh per family from the PM's National Relief Fund. The Meghalaya state government added Rs 3 lakh. Total compensation for 18 lives: Rs 90 lakh — roughly $10,800.

What is Rat-Hole Mining?Rat-hole mining is a crude, labor-intensive method of coal extraction unique to Meghalaya. Workers descend into narrow vertical shafts and then crawl through horizontal tunnels — some extending hundreds of feet — that are just 2-3 feet wide. The tunnels are called "rat holes" because only a person small enough to squeeze through can enter them. There is no ventilation. No structural reinforcement. No gas detection. No emergency exits.

According to Drishti IAS, these mines are prone to collapses, flooding, and gas explosions. Workers suffer from chronic respiratory diseases, silicosis, and life-threatening injuries. A 2010 report by Impulse NGO Network estimated that 70,000 children were working in coal mines in the Jaintia Hills alone, all below 16 years of age.

What makes Meghalaya unique is that coal mines here were never nationalized. Under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, tribal communities in the state own both the land and the minerals beneath it. The Coal Mines Nationalization Act of 1973, which brought all coal mines under government control across India, specifically exempted Meghalaya. This means any landowner can — in theory — mine their own land.

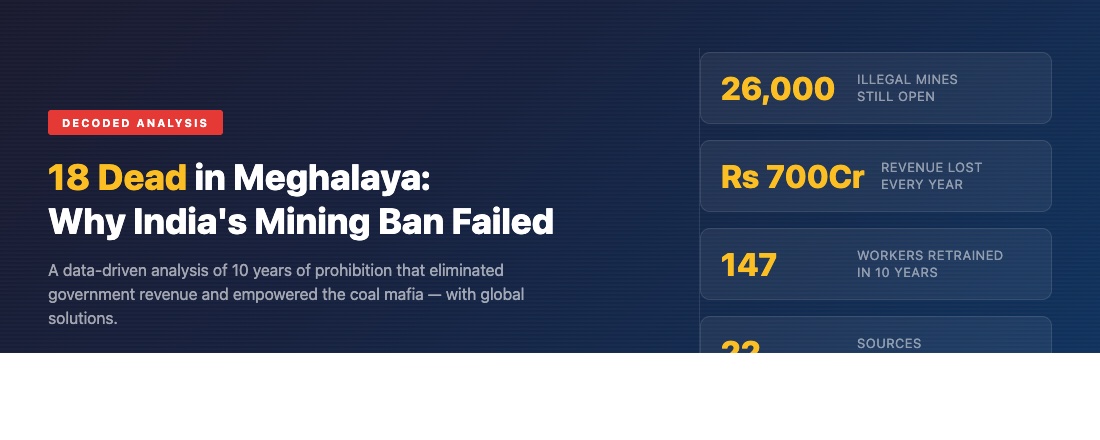

The Numbers Don't Lie: A Decade of Failed PolicyOn April 17, 2014, the National Green Tribunal banned rat-hole mining in Meghalaya. The Supreme Court upheld the ban in July 2019. The stated goals were to protect the environment and save workers' lives. Ten years later, here's the data:

| Metric | Before Ban (Pre-2014) | After Ban (2014-2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Government Revenue | Rs 700 crore/year | Rs 0 (mining is "illegal") |

| Mining Activity | Legal, unregulated | Still happening — illegally |

| Safety Standards | None (no oversight) | Even worse (can't regulate the illegal) |

| Worker Protection | Minimal | Zero — workers can't report injuries |

| Major Fatalities | Periodic | 2018: 17 dead (Ksan), 2026: 18 dead (Thangsku) |

| Rat-Hole Mines | ~26,000 | 26,000 still unclosed (HC panel, 2024) |

| Coal Trucks Intercepted | N/A (legal) | 1,000+ in 2024 alone |

| Illegally Mined Coal Found | N/A | 1.92 lakh metric tons (aerial survey) |

The data tells a stark story. A Meghalaya High Court panel found in 2024 that all 26,000 rat-hole mines remain unclosed a full decade after the ban. Chief Minister Conrad Sangma himself admitted the state loses Rs 700 crore in royalty revenue every year — money that now flows entirely to illegal operators.

India has seen this pattern before. Consider the evidence from other prohibition experiments:

| Ban | Goal | Actual Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Gujarat liquor ban (1960) | Eliminate alcohol consumption | Surat alone consumes 50,000 liters/day illegally |

| Bihar liquor ban (2016) | Reduce domestic violence, health harm | 500+ deaths from toxic bootleg liquor (NCRB) |

| Meghalaya mining ban (2014) | Protect environment, save lives | 26,000 mines still operating, 18 dead in 2026 |

The pattern is consistent: blanket bans don't eliminate demand — they eliminate oversight. The Wire reported that the NGT's own loophole — allowing transport of "already extracted" coal — was exploited to continue illegal extraction under the guise of transporting old stockpiles. According to Economic and Political Weekly, the coal business remained fully active five years after the ban, with thousands of overloaded trucks lining the Shillong-Guwahati highway.

The Scroll.in investigation revealed a crucial finding: it's not livelihood concerns but fear of the coal mafia that drives illegal mining. A police sub-inspector and an officer-in-charge who interfered with illegal coal transportation died under mysterious circumstances. Activists investigating illegal mining have received death threats.

As the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) concluded from studying similar bans worldwide: "Prohibition and criminalization were not effective and failed to make meaningful progress in managing the sector."

The Cost of a Life vs. The Cost of a LivelihoodHere is the uncomfortable arithmetic that India's policymakers must confront:

| Category | Amount |

|---|---|

| PM compensation per death | Rs 2 lakh ($2,400) |

| State compensation per death | Rs 3 lakh ($3,600) |

| Total for 18 deaths | Rs 90 lakh ($10,800) |

| Annual revenue lost to ban | Rs 700 crore ($90 million) |

| Money circulation lost annually | Rs 4,000 crore ($500 million) |

| Workers trained for alt. livelihoods (10 years) | 147 people |

In 10 years, the state has trained 147 people for alternative livelihoods through its skill development program — in an industry that employed tens of thousands. Meanwhile, the District Mineral Foundation (DMF), India's own mechanism to fund mining-affected communities, collects Rs 82,370 crore nationally from mining royalties. But because Meghalaya's mining is illegal, the state contributes nothing to DMF and receives nothing from it.

The perverse incentive is clear: it is easier and cheaper to compensate the dead than to create viable livelihoods for the living. Rs 90 lakh for 18 lives is a rounding error against Rs 700 crore in lost annual revenue that could have funded schools, hospitals, safety equipment, and job training.

Those Who Defend the Ban

- NGT ban was necessary to stop environmental devastation — acid mine drainage destroyed rivers and water sources

- Rat-hole mining is inherently unsafe and cannot be made safe at any cost

- Environmental activists oppose even "scientific" mining, arguing Meghalaya's ecology cannot sustain extraction

- The problem isn't the ban — it's enforcement; the state government has failed to implement court orders

Those Who Say the Ban Failed

- 26,000 mines unclosed after 10 years proves the ban is unenforceable

- Rs 700 crore/year in lost revenue now goes entirely to the coal mafia

- Workers have no legal protections when the entire industry is underground

- CM Conrad Sangma: "Alternative livelihood can stop illegal mining" — but alternatives were never created at scale

Colombia identified three practical routes to formalize illegal miners: operating contracts, formalization subcontracts, and devolution of mining areas for subsequent titling. Ghana, the first African country to recognize artisanal mining as a legitimate livelihood (in 1989), created a framework of licenses, cooperatives, and technical assistance. Both countries found that bringing miners into the formal economy was more effective than pushing them underground. (IMPACT, World Bank)

2. Tribal Co-Ownership — Australia and CanadaAustralia's Gulkula Mining Company is the world's first Indigenous-owned and operated bauxite mine. Canada has over 520 formal agreements between mining companies and Indigenous communities covering employment, revenue sharing, environmental stewardship, and cultural heritage protection. The UN-recognized principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) ensures Indigenous communities have veto power over mining on their lands — but also the right to benefit from it. (ICMM, OECD)

Meghalaya's Sixth Schedule already gives tribal communities ownership of land and minerals. The framework exists — it just needs to be channeled into formal tribal mining cooperatives with government safety oversight and transparent revenue sharing, rather than banned entirely.

3. Cooperative Mining — BoliviaBolivia's Kantuta Gold Mining Cooperative started with 30 manual miners in 1984. Over the next decade, with access to credit and technical assistance, it mechanized its operations, hired technical staff, and became a sustainable employer. The cooperative model worked because it gave miners ownership, pooled resources for safety equipment, and provided a legal framework for government oversight without destroying livelihoods. (Atlantic Council)

4. Affordable Safety TechnologyModern IoT-based safety technology has made mine monitoring dramatically more affordable. Smart helmets with gas detection sensors (methane, CO, H2S) can alert miners and surface teams in real time. Low-cost wireless sensor networks can monitor ventilation in small-scale mines. Research published in PMC shows these technologies are increasingly viable for small operations. The Indian government could subsidize basic safety kits for licensed small mines at a fraction of the cost of post-disaster compensation.

A Way Forward: The Proposed FrameworkBased on global evidence and India's existing institutional tools, here is a five-point framework that attempts to balance the interests of all parties — tribal communities, workers, the state government, and the environment:

| # | Action | Who Benefits | Global Precedent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Replace ban with regulated small-scale mining licenses | Govt (revenue), Workers (legal protection) | Colombia, Ghana |

| 2 | Mandate tribal cooperative ownership | Tribal communities (wealth stays local) | Australia (Gulkula), Canada (520+ agreements) |

| 3 | Subsidize safety equipment for licensed mines | Workers (lives saved) | IoT/Smart helmets, gas sensors |

| 4 | Activate District Mineral Foundation for Meghalaya | Communities (health, education, skill development) | India's own existing DMF mechanism |

| 5 | Fast-track scientific mining (50+ sites in 2 years) | Govt, Workers, Environment | Meghalaya's own Saryngkham pilot (March 2025) |

Meghalaya inaugurated its first scientific coal mine at Saryngkham in March 2025 — 11 years after the ban. Only 3 sites have been approved so far. The pace needs to accelerate dramatically if the state is serious about replacing the illegal economy with a regulated one.

Following the February 5 blast, the Meghalaya High Court summoned state officials and directed strict monitoring, regular patrolling, and action against errant officials. Union Coal Minister G. Kishan Reddy sought a report from the state government and urged Meghalaya to end illegal mining.

But summons and reports have been issued before. The real question is whether India will continue to repeat the cycle of tragedy, compensation, outrage, and forgetting — or finally pivot from prohibition to regulation.

The Bottom Line

The Meghalaya coal mine blast that killed 18 workers is not a failure of enforcement — it is a failure of policy design. A blanket ban imposed in 2014 has not stopped a single mine from operating. Instead, it has eliminated government revenue (Rs 700 crore/year), empowered the coal mafia, stripped workers of legal protections, and made safety oversight impossible. Global evidence from Colombia, Ghana, Australia, and Canada shows that formalization — not prohibition — is what protects both workers and the environment. India already has the institutional tools: the Sixth Schedule for tribal ownership, the DMF for community welfare, and a pilot scientific mine at Saryngkham. What it lacks is the political will to choose regulation over a ban that exists only on paper.